The demands for the greening of electrical power are increasingly strident, no more so in Asia. But does the build up of nuclear generators pose an even bigger threat than carbon emissions? Melissa Low explains.

Singapore. 9 May 2011. Following the 9.0-scale earthquake and tsunami that hit northern Japan on 11 March, emergency forces are still trying to minimise radioactive leakage from the wrecked Fukushima power plant. In the weeks following, several earthquakes measuring between 5.0 and 7.0 on the Richter scale occurred in Taiwan, the Philippines, and Afghanistan and most recently in Myanmar. These earthquakes all have one thing in common – the Eurasian plate.

The Eurasian plate is a tectonic (Earth’s mantle) plate which is under most of continental Europe and Asia, and is moving at an average speed of 2cm/year (0.8 inches/year). Its collisions with the Philippines, Arabian and Indian plates have resulted in all this earthquake activity. They have also raised fears and questions about nuclear energy in SE Asia. The Fukushima power plant in Japan, before the earthquake, tsunami and catastrophic fire last MarchWith the Eurasian plate constantly ploughing into the Philippine, Arabian and Indian plates, it is safe to assume that ASEAN will never be free of seismic activity. And with the damage from the December 2004 Southeast Asian Tsunami still etched into many people’s memories, there is much reason to reconsider nuclear power generation.

The Fukushima power plant in Japan, before the earthquake, tsunami and catastrophic fire last MarchWith the Eurasian plate constantly ploughing into the Philippine, Arabian and Indian plates, it is safe to assume that ASEAN will never be free of seismic activity. And with the damage from the December 2004 Southeast Asian Tsunami still etched into many people’s memories, there is much reason to reconsider nuclear power generation.

Nuclear Power in ASEAN

Nuclear energy has been proposed in recent years to help meet ASEAN (Association of South Eastern Nations) increasingly critical energy demands while preventing irreversible damage to the environment and causing climate change. ASEAN needs to consider all possible sources of energy in order to maintain its growth momentum.

Prior to the Fukushima event, all ASEAN nations apart from Brunei and Lao PDR had announced plans to undertake nuclear feasibility studies or capacity building to meet growing energy needs. While some regard ASEAN’s nuclear power ambitions as an opportunity for continued growth and cooperation, others remain sceptical about security and environmental risks

In 1995, ASEAN entered into a Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone, or the Bangkok Treaty. This has provisions for the early notification of nuclear accidents and also indicates that members have the freedom and right to use nuclear energy towards economic development and social progress. It also reveals that issues of cost, safety, waste and proliferation need to be urgently addressed.

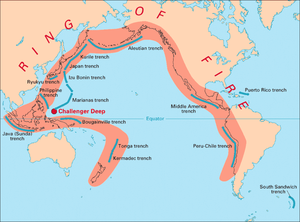

Recently, the ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation 2010-2015 put down the group’s aims to reduce regional energy intensity (energy consumed per dollar of GDP) by at least 8% by 2015 from the 2005 level. The plan also sets a strategic goal of having 15% of total power capacity installed by 2015 coming from regionally-derived renewable energy. One estimate (2nd ASEAN Energy Demand Outlook) suggests that nuclear energy could help achieve these targets by contributing 0.9% of total power capacity by 2010 and 1.6% in 2030. As a result, energy officials had reportedly been developing nuclear plans of action and monitoring mechanisms in light of the announcement. But that was before Japan’s nuclear crisis. The Pacific Ocean 'Ring of Fire' showing clearly the potential for earthquake activity across many would-be nuclear countriesDespite the establishment of the ASEAN Nuclear Energy Cooperation Sub Sector Network during the ASEAN Energy Ministers meeting in Vietnam last July, the issues of building up a strong and effective capability base and having in place safeguards and standards have yet to be clearly addressed in the public realm. The sensitive nature of nuclear technology and power plant operation demands greater regional cooperation to cover security, technological, economic and environmental aspects.

The Pacific Ocean 'Ring of Fire' showing clearly the potential for earthquake activity across many would-be nuclear countriesDespite the establishment of the ASEAN Nuclear Energy Cooperation Sub Sector Network during the ASEAN Energy Ministers meeting in Vietnam last July, the issues of building up a strong and effective capability base and having in place safeguards and standards have yet to be clearly addressed in the public realm. The sensitive nature of nuclear technology and power plant operation demands greater regional cooperation to cover security, technological, economic and environmental aspects.

Post-Fukushima Responses

As much of Southeast Asia sits astride or near the Pacific “Ring of Fire” tectonic fault lines, apprehension among the general public over nuclear energy has become palpable. However, somel governments are undeterred. Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban formally announced Thailand will halt plans indefinitely until officials have examined emergency and terrorism event plans, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia have all indicated that they are moving ahead regardless, while the remaining members have opted to proceed with caution.

Singapore, despite a national target for reducing carbon emissions by 16% by the year 2030, is hindered by the impossibility of meeting the 30km safety radius required for construction and operation of nuclear power plants. The Ministry for Trade and Industry announced that a prefeasibility study was being undertaken, but has assured the public that the nuclear option is still “far away”.

So why are Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia choosing to forge ahead? The answer might lie in their national emission reduction targets for 2020 and beyond. For example:

- Vietnam has committed to 5% per cent of electricity coming from ‘alternative’ energy sources by 2020. It is moving forward with construction of ASEAN’s first 4,000MW nuclear plant and envisages 14 nuclear reactors online by 2030.

- Malaysia’s Prime Minister announced a conditional voluntary target of 40% emissions reduction by 2020 from the 2005 level, on condition that Malaysia receives technology transfer and effective financing (potentially for nuclear options).

- Indonesia has committed a 26% (19% from the energy sector, 7% from forestry and land use) reduction in emissions by 2020, or up to 41% (15% from the energy sector, 26% from forestry and land-use) by 2020 if international assistance is offered.

Whatever the reason for pursuing the nuclear option — be it national climate change and emissions reduction targets and/or a desire to diversify and enhance energy security — Japan’s nuclear crisis has complicated Southeast Asia’s potential adoption of nuclear power, especially for the countries that are prone to earthquakes.

Big Questions Remain

While regional agreements like the Treaty of Bangkok help govern ASEAN’s nuclear path, individual countries could well lack significant capacity to deal with possible nuclear disasters. The risks of trans-boundary pollution and nuclear waste disposal also need to be addressed. One suggestion is a ‘unified ASEAN agency’ that would serve to govern the transfer and disposal of radioactive nuclear waste and address ASEAN-specific nuclear related risks.

There is no doubt much work remains to be done among ASEAN member states. This includes areas such as capacity building, public information and education initiatives, institutional, legal and regulatory capabilities. Before a safe, nuclear future for the whole of ASEAN can be considered, the fault lines remain across the region. And the Eurasian plate continues its relentless travel.

The writer is an Energy Analyst with the Energy Studies Institute Singapore, Energy & the Environment Division.

For more information: ESI Bulletin on Energy Trends and Development (Volume 4/Issue 1) in April 2011

Photos courtesy: Web sources