Review: Reef Creature Identification, Tropical Pacific by Ned Deloach and Paul Humann. A 500-page Guide on Mobile Marine Invertebrates.

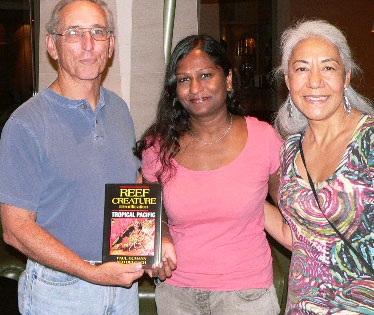

Mallika Naguran meets Ned Deloach, the co-author of Reef Creature Identification, Tropical Pacific, and his wife Anna at the launch of the guidebook in Singapore. And gets hooked by amazing discussions on marine diversity, natural selection and critter hunting.

Ned Deloach loves cryptic critters.

Singapore 30 October 2010. Ned and Anna Deloach could barely contain their excitement when describing to Mallika Naguran (in a Gaia Discovery exclusive interview) their experiences in hunting, photographing and documenting invertebrates - marine animals without backbones - for the all-new Reef Creature Identification, Tropical Pacific.

The range of mobile marine invertebrates they describe can be found in the warm tropical waters of the Pacific Ocean, ranging from Thailand to Tahiti.

Co-authored by Ned Deloach and Paul Humann, the book was first released in Singapore, Asia late October followed by a release in the US in November. The two well-known marine life naturalists, writers and photographers have authored eight other field guides and other productions over 20 years.

This 500-page reference brings to the fore some 1,600 mobile marine invertebrates with 2,000 photographs contributed by various divers (including Asians William Tan, Ivan Choong, Indra Swari, Stephen Wong, Takako Uno and Ria Tan) in a visually pleasing layout. The text incorporates taxonomic research by 40 scientific specialists, yet is descriptive enough to be easily understood by jargon-averse readers.

“The book breaks away from the scientific context and brings information to the lay people,” said Ned. “I'm sure they will be startled to see the immense population and diversity of such invertebrates.”

Simpson's Snapping Shrimp. Pic by Ned Deloach.

Ned, based in Jacksonville, Florida, was an educator and has worked extensively as a journalist and photographer for various publications. He has been diving for “just more than 40 years” since he left college in his 20s.

Anna has been a trusty partner in the making of this book by scouting the subjects. She shoots videos and films for documentaries and co-produced Sensational Seas, an anthology of rare underwater images in 2004.

Anna says the reef creature guide is not just for dive junkies, but also for everyone. “What’s groundbreaking about this book is not just the sheer numbers but the number of animals that scientists have not seen. The critters appeal even to non-divers who will be amazed to see that such creatures actually exist.”

The beauty and diversity of marine creatures including many undescribed species unfold before your eyes as you turn the chapters of this guide that even display animals up to three quarters of the page even.

“Even though this is a guide, we wanted to honour the animals by enlarging their images,” explained Anna.

Urchin carrying crab. Dorippe-fascone. Pic by Ned Deloach.

The content begins with the simplest multicellular form and progresses on to more complex biological components. Four phyla are covered: crustaceans, molluscs, worms and echinoderms.

Upfront, the book also describes and illustrates stony, soft and black corals, gorgonians, anemones, corallimorphs, sponges, hydroids, jellyfishes, ctenophores and tunicates but does not provide detailed species description of each. Rather it focuses on free-swimming and crawling marine animals without backbones. Yes, nearly 2000 photographs just on those.

Wilson's Egg Cowrie, Prionovula-wilsoniana. Pic by Ned Deloach.

You can learn how to tell the devious Wunderpus apart from the Mimic Octopus, and at the back of the book explore the world of symbiosis relationships, the wonders of invertebrate reproduction and other wondrous behavioural traits.

It took the team five years to put together this massive collection, documenting them, getting scientists to describe them and for peer review. “The new book represents our most pioneering work,” DeLoach explained. “Although quite detailed, what we have compiled only scratches the surface of the undreamed-of animals still out there waiting to be discovered.”

The Wild, Wild New Thanks to Natural Selection

I am not a big fan of nudibranchs. I kind of like the big stuff. The bigger, the better.

Flipping through the pages of this guide, however, I come across a slug barely longer than my pinky finger illuminated with Xray-like effects and ghostly branch tips. The Bolland’s Tritonia, states the picture caption, is a deep-water species that can be found in the West Pacific.

And across the page is a translucent white slug with red-orange-brown glow - the wildest creature I’ve ever seen! It is an undescribed species of Dendronotid Nudibranchs – Tritoniidae. Neither species mentioned fit into your everyday image of a nudibranch, and that’s because nature has woven its magic over time to change the physical characteristics of the creature according to environmental and biological factors. Now that caught my attention.

“Lacking the constraints of vertebrae, natural selection for these special groups of animals has gone wild,” said Ned. “We marvel at evolution through natural selection. It alters the animals so that they can survive and feed and these other habitats without so many hiding holes.”

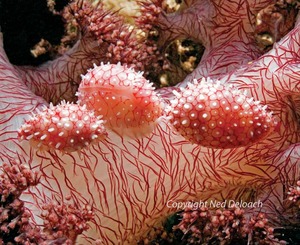

Xenia-like nudibranch carrying a commensal shrimp. Pic by Ned Deloach

Ned described how in Flores in April 2009, at just 2m deep at Mucky Mask, he chanced upon a shrimp that mimicked a hard seashell until its blue eyes gave it away. He also spotted an undescribed Aeolid nudibranch that had what seemed like pulsating Xenia soft corals on its body (see photo).

“Wallace, Darwin and Hooker and the people of their time went out and brought back all those great specimens - they got Europe alive with excitement. I wouldn’t compare myself to those greats but in this age of digital photography, by recording these animals underwater, I think our message to protect these animals will be heard” said Ned.

Ned, also a fan of decorator crabs, is keen they should get more documentation about their natural selection. “This spider crab group with velvet-like hooks all over their body clip stationary animals off the reef and hook them on their backs. This disguises their presence – not just from predators but from the inquisitive eyes of divers too. This makes the game of cryptic animal hunting even more exciting,” he chuckled.

“You have virtually got to look at everything. You do not know if they are animal- that’s their intent. Natural selection allows them to live and proliferate in these varied environments.”

At the interview, photographer Ivan Choong shared how he chanced upon the rare Teddy Bear crab in Manado house reef. He remembered how in the heat of the moment, he screamed through his regulator.

"Look at this excitement!” laughed Ned. “We love it when people have a passion for natural history.” It turned out that Ned had never seen that crab species (Poludectus cupulifer) before and I saw his eyes sparkle. Even though you'd think he would have had enough of turning over “10 cadgillion rocks” in search of cryptic animals - well apparently not!

Teddy Bear crab, Polydectus cupulifer. Pic by Ivan Choong.

“There are many things I have yet to see. I don’t care how many rocks we have to turn over. There’s always a creepy crawly to be discovered,” said Ned, who sticks his nose into rubble, coral fragments, sea grass meadow, and of course muck on a regular basis.

Photographers’ Role in Protecting the Oceans

Sadly, Ned and Anna have also witnessed degradation of habitats due to destructive fishing practices. This results in biomass loss in some parts, evident in especially far eastern Indonesia.

“We (humans) keep pushing and pushing the environment and the oceans; maybe this book will be one small step in the endeavour to protect it,” said Ned. “I hope that this might give people some ideas on what there is underwater that they could protect.”

He explained how everybody can support this initiative by capturing and recording amazing new finds when scuba diving. “The role of photographers is very important in documenting natural history… they can send the photos to the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) that I started with Paul Humann in 1990,” said Ned.

REEF promotes understanding of marine populations through a volunteer fish monitoring program and surveys. “We have thousands of photos posted by recreational divers since and data from 140,000 marine surveys on the site,” explained Ned. Anyone can use the data. Divers and non-divers alike can become members of this marine conservation program, so do sign up.

Writer (middle) is now a macro convert, thanks to Ned and Anna Deloach.

This book's objective is pretty clear. Reef Creature Identification, Tropical Pacific is designed to show the beauty of ocean creatures, many of which have never been seen before, with the hope that they will be treasured. Many more have yet to be discovered even in the shallows.

“We are the first generation to see these underwater,” said Ned. “We hope that the book will be a worthy ambassador of the natural history of the marine critters that we so love.”

I was delighted to receive a press copy of the book, in which Ned signed “Dear Mallika, I hope you find every critter in this book!”

You betcha.

Photography courtesy of Ned Deloach and Ivan Choong.

Reef Creature Identification– Tropical Pacific is available in Asia through DiveBooks.Net (www.divebooks.net) for SGD75 and elsewhere at New World Publications(www.fishid.com.)

With thanks to Ivan Choong for facilitating the interview.

Take Action: Restore Coral Reefs and Prevent Beach Erosion with Biorock

Shark Fin Ban in Hawaii to Prevent Overfishing and Extinction of Sharks

Breeding Pompano Commercially With Low Environmental Impact

Sturgeon More Critically Endangered Than Any Other Species

Bangus or Milkfish Cultivation Systems in the Philippines

Seahorses Exploited, Overfished for International Trade

Popular tuna are over-fished, in danger of extinction

Thousands of Endangered Turtles Rescued at Philippines Hatchery

Cultivating Groupers in Fish Farms Ends Dynamite and Cyanide Fishing

Cultivating Mangrove Snappers Averts Destruction of Mangroves

Reviving Bangus Farms and Fishing Industry Hit by Typhoons

Farming of Sea Cucumbers For Environmentally Friendly Industry

Seaweed, Versatile Marine Resource for Food, Animal Feeds, Fertilizers, Medicine

Seabass Hatcheries Sprout, Easing its Cultivation

Is Eating Tilapia Nutritious or Harmful to Health?

Oceans in Crisis due to Global Warming, Over-fishing and Pollution

Tuna Species Under Threat With Over-fishing, Exploitation On for Big-eye and Yellowfin Tuna

Life Reef Fish Trade Threatens Lapu Lapu or Grouper Population

Unless something is done soon, the succulent lapu-lapu will soon no longer be part of the menu in your favorite Chinese restaurant. The reason: the supply is facing imminent collapse!

Forty years of unregulated cyanide and dynamite fishing, in addition to the rising trend to target vulnerable spawning areas of lapu-lapu, have all contributed to the rapid disappearance of the highly valued fish.

Most of the spawning areas of lapu-lapu can be found in Palawan, the country’s last frontier. Palawan and its territorial waters host some of the most productive yet exploited fisheries on earth, according to World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), a global conservation group.

“Unless we preserve remaining wild stocks today, Palawan’s fisheries will not be able to replenish and will collapse by 2020,” deplored Dr. Geoffrey Muldoon, live reef fish strategy leader for WWF’s Coral Triangle Program.

The Philippines is considered to be the centre of the Coral Triangle, a region between the Pacific and Indian Oceans that harbors 75 percent of all known species of plants and animals that thrive among coral reefs.

The Palawan live reef fish trade has supplied business lunches and expensive banquets in Asia since the 1980s, bringing more than 100 million dollars a year to fishermen who often use cyanide or explosives to stun the fish.

“Our wild stocks for lapu-lapu are fast becoming depleted because of overfishing as a result of their high price and big market abroad,” said Dr. Rafael D. Guerrero III, executive director of the Laguna-based Philippine Council for Marine and Aquatic Research and Development (PCAMRD).

Citing surveys, Muldoon said that 60 percent of all groupers taken from Palawan’s reefs are juveniles, an indication that adults have been heavily depleted and that as a whole, the ecosystem has been “badly over fished.”

Less than five percent of Philippine-caught lapu-lapu are sold locally, as these were often rejected by foreign importers, the WWF said in a statement. Unlike most other fish species which are chilled or frozen, groupers are generally sold alive in markets.

The fish was named after the national hero who killed Ferdinand Magellan in the Battle of Mactan. But internationally, the fish is known as grouper. The name comes from the word for the fish, most widely believed to be from the Portuguese term, garoupa. The origin of this name in Portuguese is believed to be from an indigenous South American language.

Grouper is one of them most expensive fish in the market and it is valued because of its texture and taste as well as its great potential in the aquaculture market. The demand of the groupers in the international market is fast growing particularly in Hong Kong, Japan, and Singapore and mainland China.

In Hong Kong, lapu-lapu fetches up to P6, 000 per piece. “Most Hong Kong people now choose to eat grouper because of the firm flesh. It’s tastier,” Ng Wai Lun, a restaurant owner in Hong Kong, told a news agency. “Farmed fish is less tasty and fresh.”

Just for the information of the uninformed, in the blockbuster movie, Drunken Master, steamed grouper was one of the many dishes Jackie Chan’s character requests during an attempted meal-theft.

Groupers are mostly solitary–often lethargic looking–reef predators from the family Serranidae. They have a stout body and a large mouth. They are not built for long-distance fast swimming. They can be quite large, and lengths over a meter and weights up to 100 kilograms are not uncommon. They swallow prey rather than biting pieces off it. Habitually, they eat fish, octopus, crab, and lobster. They lie in wait, rather than chasing in open water.

The fish’s mouth and gills form a powerful sucking system that sucks their prey in from a distance. They also use their mouth to dig into sand in order to form their shelters under big rocks, jetting it out through their gills. Their gill muscles are reportedly so powerful, that it is nearly impossible to pull them out of their cave if they feel attacked and extend them in order to lock themselves in.

According to the filmmaker Graham Ferreira, there is at least one record, from Mozambique, of a human being killed by a grouper. Arthur C. Clarke wrote that while scuba diving in an inlet on the coast of Sri Lanka, he saw a grouper about 20feet long and 4feet thick side to side, living in a sunken floating dock.

A recent survey conducted by the WWF showed that 20 of 161 species of grouper, a reef fish that makes up a large part of the Coral Triangle’s live fish trade, were threatened with extinction.

The 20 include the squaretail coral grouper and humpback grouper, which are a popular luxury live food in Asian seafood restaurants, according to the world conservation organization.

In Palawan, catching live fish, including groupers, is easy. Crush a couple of sodium cyanide tablets into a squeegee bottle of water, dive around a coral reef, find a fish you fancy, and squirt the toxic liquid into its face. The mixture stuns the fish without killing it, making it easy to catch in a net, or even by hand.

With cyanide you can catch dozens. But the method proved to be devastating: chronic overfishing that is undermining the country’s ability to feed itself. “Look at the places where live reef fishing started a decade ago; they have all been fished out now,” lamented a WWF staff. “The traders and the migrant fishermen just scoop it all up and move on.”

The future seems bleak. “Our lapu-lapu fishery does not contribute much to our fisheries production,” noted Dr. Guerrero. “Small pelagics such as anchovy, sardine, and mackerel constitute the bulk of our marine fisheries.”

However, the PCAMRD head believes that there is still hope for lapu-lapu fishery. “To conserve them, fishing pressure should be regulated and marine reserves where they are protected should be maintained,” he suggested. “Breeding them in captivity is another way.”